The Birth of Comedy out of the Suicide of Tragedy

Or:

Letterman and Leno

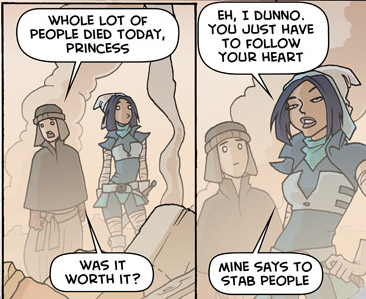

Nietzsche felt that the rise of the comedic play signaled the end of the traditional Greek tragedy, and with it, great art. However, this new comedy still retained much of the old theory behind his conception of the tragedy. The two primitive artistic impulses represented by the Gods Apollo and Dionysus are still critical, but in comedy the old duality is split into a ternary system with Aesthetic Socratism opening up a ground in between. This middle acts as sounding board that evaluates the merits of the artistic impulses against the average and normative feelings of everyday life. With this new and utterly familiar impulse, the old Gods can at best be hinted at, as the everyday normality that Socratism brings cannot be escaped from.

Tragedies were necessarily made from the interaction of two opposing impulses. Apollo represented the dream state that employed forms and images to generate grand illusions. This aspect of the tragedy gave the general form of the story: Mount Olympus, oracles, Gods, etc., as well as the literary style employed. Dionysus, however, embodied the drunken ecstasy that strips away all representation and reincorporates the body into the world without intermediate thought or consideration. Solely content is given to the tragedy by the Dionysian component. In this Nietzschean tragedy the characters were all merely masks of Dionysus thrust into an Apollonian context. With this union of the Apollonian forms with the Dionysian content comes forth a work of tragic art.

When tragic art was created in such a way, Nietzsche held that it was beyond our mental faculties to completely comprehend it. He says on page 80 (of The Birth of Tragedy and the Case of Wagner, trans. W. Kaufmann), “Even the clearest figure always had a comet’s tail attached to it which seemed to suggest the uncertain, that which could never be illuminated,” and that there was always an “incommensurability in every feature and every line.” Regardless, the tragedies enjoyed almost universal success.

Socrates did not like the old tragedies though. He held that, “Knowledge is virtue,” (84) and as a corollary, “To be beautiful everything must be intelligible,” (ibid.). Under this scheme the absolute lack of intelligibility that was fundamental to the tragedy was no longer of first-rate artistic value. Moreover the new requirements, “man only sins from ignorance; he who is virtuous is happy” (91), made tragedy low, base and to be avoided as sinful and without virtue. The very aspect that previously gave the tragedy its greatness became its downfall in Aesthetic Socratism.

With this full reversal of values, the suicide of tragedy becomes clear. Neither the Apollonian nor Dionysian can withstand this change. The Apollonian is an impulse towards the ideal, to the form of the world and cannot be fully explained insofar as the ideal itself is unreachable; the Dionysian attempts to connect life in a more intimate way with its surroundings, such that the impulse is more basic and prior to rational thought.

Where can Nietzsche go from here? He has seemingly broken any connection to his theory with the advent and incorporation of Aesthetic Socratism. However, not all is lost. As the tragedy declined in popularity, a new form of entertainment arose: the comedy. In the comedy, the plot revolved around daily Greek life. Every aspect, every character, every twist and turn of the plot was readily understandable and identifiable to the audience. But how could this be entertaining, especially with the tragedy still in recent memory? Were the Greeks so sick of tragedy and primed for Socrates arrival that they were prepared to abandon all their old aesthetics for new ones?

Nietzsche does not think that the comedy and Aesthetic Socratism killed the old artistic impulses, but instead somehow bastardized then into being merely secondary. In this way both the Apollonian and Dionysian could be retained in some respects, so long as an undercurrent of overall intelligibility was maintained. What then does Aesthetic Socratism amount to, especially in terms of some sort of substructure for the old artistic impulses to be reconstructed on? It is the firm belief that between knowledge and reason one can be “liberated from the fear of death,” and in doing so, essentially make all of life “comprehensible and thus justified,” (96). Therefore the baseline for the artistic impulses must be everyday logical and scientific truths at home with any person endowed with knowledge and reason.

Even though the fundamental belief of Socratism has now been brought out, it is still not clear how this confidence in our abilities to understand can produce anything artistic. However, it is illegitimate to ask for a remnant of the old tragic theory under the new schema: tragedy is long dead. Instead one must take Aesthetic Socratism while still under the influence of the past: the Apollonian and Dionysian must evolve to incorporate intelligibility, as intelligibility cannot incorporate them. Looking down from the height of the Gods, how does this impulse for the everyday human endeavor appear? As our finite reality enters our currently God-like consciousness, “it is experienced as such, with nausea,” (60). This sickness brought on by the absurdity of human existence in comparison with the far reaches of our dreams and ecstasies can only be made bearable again by art: “the comic as the artistic discharge of the nausea of absurdity,” (ibid.). Therefore it is the old artistic impulse, twice used, that produces of a comic work of art: once to conceive of Socrates as a new God (82) and then again to escape from him.

Hence the artistic impulses are not lost in comedy, but what has happened to them in their second iteration, the re-conception of the everyday? However big the “enormous driving-wheel of logical Socratism… behind Socrates,” (88) actually is, the best it can muster is reason (logic) and (scientific) knowledge. Nietzsche realizes that with these two constraints, logic and science, “The Apollonian tendency has withdrawn into the cocoon of logical schematism… the Dionysian into naturalistic affects,” (91).

Finally we have Nietzsche’s conception of a comic art: tragedy restrained by everyday life. But the above formulation is only accurate for one spectator: the playwright. There is no comedy for Euripides; there is only his bathetic tragedy (the comic doesn’t normally laugh at his/her own jokes). Every other member of the audience, on the other hand, does not have the same perspective, but the opposite. They side with that which they know, the Socratic championing of the everyday, and hence the comic art becomes the everyday constrained by tragedy. This brings the Apollonian and Dionysian together as two different impulses away from the Socratic, giving innuendos towards something great and ultimately tragic, but now unreachable.

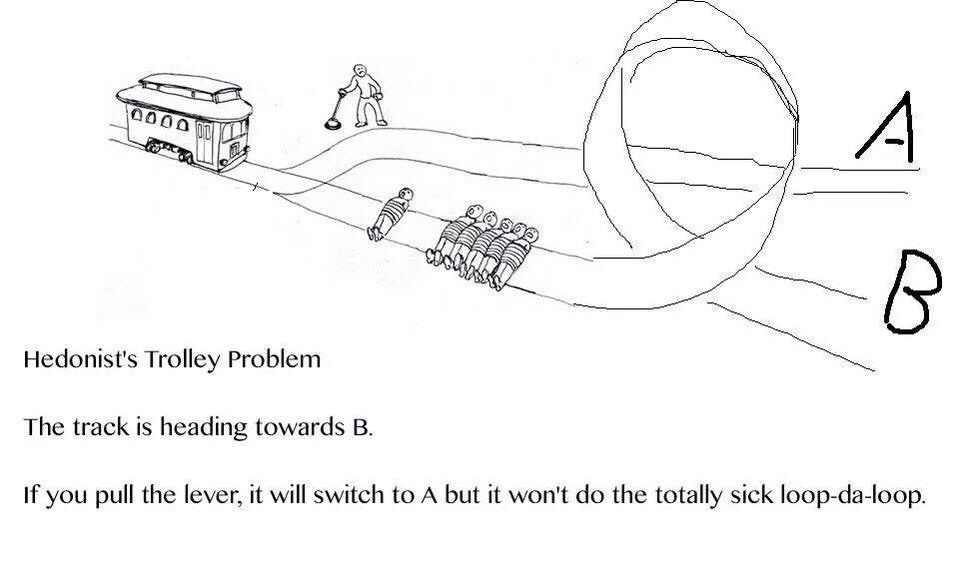

Now we can see the general form of the comedy is different than the tragedy. Tragedies were born out of the two artistic impulses and hence could really only take one form: Apollonian form with Dionysian content. With the advent of the third and now critical impulse, two new relations were created: Dionysian to Socratic and Apollonian to Socratic. In the case of the first relation, the Dionysian impulses truly cannot give form, and so the Socratic must then act Apollonian, but only in contrast to the Dionysian. Secondly, as Apollonian impulses cannot give content, the Socratic must then be a surrogate Dionysian; again, not in a true sense of the term Dionysian, but in mere contrast, as a pseudo-god. In so far as the Socratic only acts as a foil, the contrasting impulse is also limited. This signals two distinct forms of comedy, using the Socratic as a substitute for weak comparison.

However, from the Socratic spectator’s point of view, the Apollonian and Dionysian are secondary. Instead of being a foil for the Gods, the Socratic is elevated to Godly status by its ability to make clear the artistic impulses. The Dionysian and Apollonian have now become intelligible: when the Socratic, the everyday, acts as content, then we can know the form in its contrast to the Socratic to be Apollonian, and conversely when the Socratic acts as form, the content is the Dionysian in contrast. Hence Nietzsche volunteers, “Cool, paradoxical thoughts replacing Apollonian contemplation-and fiery affects, replacing Dionysian ecstasies,” make up the comedy from Socrates Cyclops eye, “and in no sense [are] dipped into the ether of art” (83).

Critically, we must wonder whether Nietzsche’s theory is viable. Late night comedy is prime hunting ground, but we must start with the Socratic understanding since it is the only intelligible foundation we have.

“The Tonight Show” with Jay Leno on NBC seems to be a prime example of Dionysian comedy. Leno always starts off the show by shaking hands with the audience. Then he goes into a monologue of jokes followed by some sketches. The show then moves into an interview stage with celebrities and ends usually with a musical performance and sometimes a standup comic. This all seems very normal and could be any sort of variety show. However, this is the first clue to Leno’s comic insight: a Dionysian comedy requires that the form be entirely mundane and everyday, entirely Socratic. Now the way he even starts, by shaking hands with the audience, can be seen as part of his comic routine: it binds him to the everyday people in a communal way. Next comes the monologue. Perhaps not every, but nearly all of the jokes have a similar format: the build-up to the punch line is in entirely normal, everyday speech; he might as well be a reporter. But then comes the punch line: it has some sort of strong reference to some fiery affect, a feeling of drunken ecstasy. For example, a few days ago (probably on or around 4/18) he began a joke by saying how the troops searching Saddam Hussein’s palaces had recently found hordes of pornographic magazines. The punch line: the magazines are being referred to as “weapons of mass–turbation.”

After the monologue comes a skit or two. Some sketches are regulars and appear consistently on certain nights. Every Monday night a bit called “Headlines” is done. Very simply, Leno collects clippings sent to him from around the country that he finds funny due to a misprint or just carelessness and puts them on display for everyone to see. Each headline itself is inconsequential or just an honest mistake and always found in some legitimate source, but when he puts his spin on them, they take on extra Dionysian shades of meaning that were not meant to be there. Tonight (4/23), Leno had a debate similar to the new “Point, Counterpoint” debate on “60 Minutes”. Instead of having two political rivals, he brings together two relative morons and asks them simple questions. The joke seems to be in the universal joy of not saying the stupid things that they say: their ignorance is laughed at, but it only is funny in the setting comparable to simple, serious, everyday questions asked.

“The Late Show” with David Letterman on CBS makes for an excellent illustration of Apollonian comedy. He too begins his show with a funny monologue before having some skits and eventually interviewing guests and ending with some musical performance. However, his monologue is much shorter than Leno’s. Instead he moves directly into skits and stunts. Sometimes he even interviews a guest before the stunts. Recently he has been doing a short little segment that pokes fun at Dr. Phil the TV psychologist. It is called “Dr. Phil’s Words of Wisdom” and essentially consists of a short cut of Dr. Phil saying something apparently stupid. The funny thing about the segment is not the clip itself, which is obviously taken grossly out of context, but the entirely new context given: words of wisdom. This contradiction in name and content is the Apollonian impulse away from the Socratic; the displacement of the form of presentation is the Apollonian comedic insight.

Letterman also has a great segment called, “Is this anything?” A performer does an act and then Letterman and Paul Shaffer decide if what the performer did was either something or nothing. The absurdity of the situation is that the whole thing is treated as a kind of game show, as if the performer could lose something by the act being determined to be nothing. All the while, Letterman has two performers, the “Late Night Grinder Girl” and the “Late Night Hula-Hoop Girl”, and models flanking the person judged, not as a distraction, but as to create an even grander sense of performance. This great build up to a relatively inconsequential decision again shows the Apollonian comedic insight.

Lastly, Letterman’s “Top Ten” is a prime example of the Apollonian form with Socratic content. Nothing in the “Top Ten” is usually that far-fetched or unusual. The genius was to group these ten things together and to order them for a purpose, and that is where the comedy was created.

Many more examples from both shows can be given to support the above claims. Interestingly, both comics are not limited to only their own style of comedy even if they are reluctant to venture too far. The Socratism each uses gives them access to a reflection of the artistic impulse they are unfamiliar with and the illusion that they “know” it. Recently Letterman made a Dionysian joke: he began by commenting on how we could determine if Saddam Hussein had died under rubble since we had his DNA. Then he proceeded to show us a picture of the person who obtained the DNA: Monica Lewinsky. As soon as the joke was over, he began to apologize: the form was not up to his usual Apollonian standards and that made the punch line a comparative low blow to the rest of his jokes. Interestingly Leno had made a similarly “tasteless” joke the same night; his response was to announce that he would not apologize.

Leno too makes some attempts at Apollonian comedy. He has a “Jeopardy” style skit in which he has comedian fill the roles of people in the news. The comedians give answers, reflective of their character, to legitimate questions. This phony game show setup would be similar to a game Letterman might play, but Leno is unsure of this kind of comedy and guarantee’s laughs by having comedians fill the roles. The above-mentioned “Point/ Counterpoint” could be seen as an artificial and Letterman-like game as well. Leno does not focus on this though: the setup is still a current event, not an arbitrary construction as “Is It Anything?” is, and finds the comedy in the content, the contestants.

Comedy, sparked by the tragic and mediated by everyday life, has a special place in between great art and not being art at all. To incorporate Socrates the Gods Apollo and Dionysus had kids: Letterman and Leno. These lords of late night talk shows are able to handle the tragic Godly insights as well as keep one hand on the pulse of the nation. In the synthesis that followed, each developed a unique style antithetical to the other. Leno takes things out of context; Letterman puts things out of context. Ultimately neither could survive without the other, just as Dionysus and Apollo need each other. However, the inheritance of Aesthetic Socratism dooms each into attempting, against their best instincts, the comedy of the other.

tks for the effort you put in here I appreciate it!